Notes from Startup Workshop Class at Davidson College

Intro

I recently led a one-hour classroom discussion on startups for my five-year reunion at Davidson College. This post is a summary of the notes I used to plan the session. Many of the ideas here were inspired by Paul Graham’s essays and Scott Galloway’s book The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. I’ll try to link to specific essays and excerpts when relevant.

What is a startup?

Which of the following companies are startups?

- Slack

- Instacart

- Uber

- Wikipedia

- Amazon

- AWS

- Davidson College

- Y Combinator

- your local barber shop

- Tesla

With many more examples, I don’t necessarily have a correct answer, and I think it quickly becomes clear that we all have a vague notion of what a startup is, but it’s surprisingly tricky to pin down to classify specific companies. Possible criteria include age of company, need for external investment, for-profit, privately-held, high growth, small number of employees, small revenue, novel problems, novel solutions, or non-obvious success. There’s not a consistent agreement here, and if you ask someone in Silicon Valley, New York, and Florida about which of these criteria are essential for a startup, you may get very different answers.

The point here is that startups take many shapes and sizes and there is no one “correct” recipe. As far as when a company is a startup and when it isn’t, I tend to agree with Paul Graham’s assertion that startup = growth. The defining characteristic of a startup, in my opinion and according to Paul Graham, is the goal of selling to a large market. This shapes the behavior and output of the startup in defining ways because rather than serving only a local or easily-satiable need, startups need to make something lots of people want in a way that can reach and serve all those people. The key is scale and it necessitates that startups be focused on growth. I posit that this, whether explicitly defined or not, is the viewpoint of startups in Silicon Valley culture, and a very different meaning may be understood elsewhere.

The Right Idea for a Startup

I often hear people say they are interested in entrepreneurship but they don’t have an idea. This is probably just a convenient excuse rather than the real reason, and I think it’s a mistake. If you’ve said this, hopefully this section helps encourage you to believe that if you are really committed to starting a company, having a brilliant new idea is not a prohibiting factor.

In the next section of my workshop, teams of 2-3 people created and pitched a startup idea. I gave some pointers on how to come up with ideas, but I also wanted to emphasize how having the right startup idea is often over-emphasized by many potential founders. Within 15 minutes, every group had a reasonably compelling business idea, so it’s not as difficult as people like to say. Additionally, many companies change their product and core idea more than once before they find growth.

I’ve noticed that founders who start a company without an idea can build incredibly successful businesses because, in my opinion, they take the time to critically reflect on any prospective ideas, and they aren’t too attached to a single business plan, so they are willing to pivot until they find the best product.

With that in mind, I did give some tips to help the groups more comfortable planning their startup idea. Many of these ideas are borrowed from a presentation by Dalton Caldwell and Paul Graham’s essay on startup ideas.

How to Generate the Idea

- It’s best have an organic idea rather than a forced idea because organic ideas tend to address real needs. Organic ideas are those where in your previous job you found yourself saying, “Why doesn’t someone make x? If someone made x, we’d buy it in a second.”

- One barrier to generating organic ideas is that many people don’t give themselves the opportunity to relax or let their mind wander. #The mental drift is often what leads to the subconscious drifting to real things you want or problems you have (I’m not a psychologist). If you’re always thinking about your day-to-day work and immediate plans, it’s difficult to exercise your creative mind. Many people find this creativity in the shower or while on a quiet walk. If you’re listening to the latest podcast, though, your mind probably isn’t relaxing.

- Successful startups typically take at least 5 years. What’s important then may be very different than what’s important today. Live in the future, then build what’s missing.

- Don’t filter out difficult and unsexy ideas. Things that are hard are often ripe for innovation, or at least they can often be pilfered for profit by the grit and elbow grease of a startup. As for sexy ideas, many people have tried them, and the unsexy ones are often hidden in plain sight.

- Don’t confuse a company’s mission statement with it’s original idea. Mission statements are often filled with marketing jargon and were created much later in a company’s life. They can sound vague and intimidating because they are well-crafted and difficult to write cold. Google didn’t always set out to “organize the world’s information.” At first, they just wanted to make searching the Internet suck less.

- Even if you still don’t have a sure-fire organic idea, don’t let that be the reason you don’t start. Try something, anything, and be open to new ideas as they come. In fact, build something bad and try to sell it. Then listen obsessively to your customers and potential customers because they will tell you what they want. Often, trying to sell a bad idea is the only way to get people to tell you what they really care about.

- Find not only an idea that will grow but rather a market that is growing.

- Consider business-to-business (B2B) products. In my non-data-driven observations, many new startups are consumer products because that’s where the founders have experience. Yet, the B2B startups are often disproportionately successful. Consumer products can be huge and influential, just don’t limit yourself to them.

- If your idea sounds like a bad idea, it may flop, OR this may be a signal that your idea is in fact a huge winner. Many, many early startup ideas sounded terrible at the time, yet they turned into some of the most powerful companies today. Many people laughed at Larry Page and Sergey Brin for wanting to build “just another search engine” in a crowded and not-so-profitable market, yet they built a better product and redefined the online ad business with ad auctioning. Facebook was merely a “copy of MySpace” until they built a reputable status game by first growing within prestigious universities. AirBnB wanted to allow people to let strangers sleep in their homes, and AirBnB struggled to receive early funding because who would want a stranger sleeping in their own home.

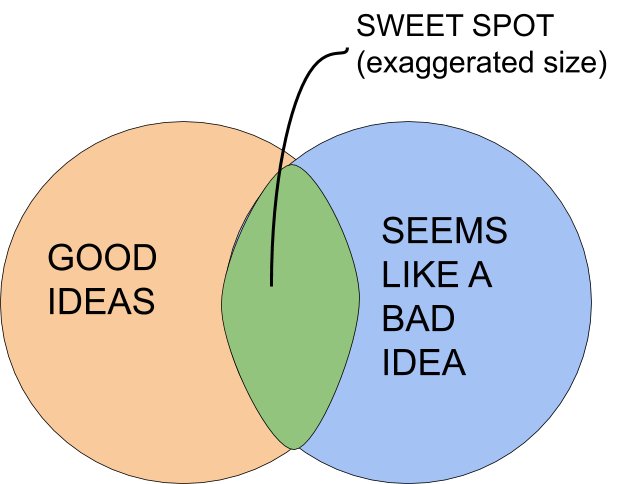

This divide is another reason why startups and startup investing are high risk and high reward. Startup success is simply difficult to predict. So don’t be dismayed when family, friends, and investors laugh at your idea. The image below is a visual representation, described by Paul Graham on account of Peter Thiel.

Do take a moment though to consider the fallacy of survivorship bias in my prior paragraphs. Google, Facebook, and AirBnB all had their own struggles to convince investors, so all bad ideas must become giant successes, right? Just remember that there are plenty of companies that started with seemingly bad ideas, and those companies failed for one reason or another, idea or not. Then, use the next list below to evaluate your own idea and convince yourself why yours is one that is actually good and isn’t as bad as it sounds.

The sweet spot for startup ideas is in the small overlap between good ideas and ideas that seem bad.

How to Evaluate Ideas

Here are some very simple questions and tips for a sanity check on your startup idea. Many are borrowed from Dalton’s slides linked earlier.

- Do people want this?

- How do you know?

- Has anyone tried this before?

- If yes, why didn’t it work?

- If no, are you sure people want it?

- Why are you excited about working on this?

- Is your excitement contagious?

- Why are you the team to do this?

- It’s better to have an idea that seems small but solves an immediate “hair-on-fire” problem than to have a really big idea with questionable need.

- Good ideas often seem small and trivial at first. Don’t worry too much about the “size” of your idea Focus on it being immediately useful to a small group of people, and guide yourself based on how much your users value your product.

- Would you still use this if you hadn’t built it?

- Can you explain your business in 1-2 sentences?

- Can your business grow to be a $1 billion business? See 5-Minute Market Analysis

Pitching your Startup

At every stage of a company, it’s essential to able to describe the product clearly and concisely, whether pitching to investors or marketing to customers. If the idea is too complicated to describe in 1-2 sentences, you probably need to try harder, and if it’s still too complicated, then this is a signal of an unsuccessful idea. I wrote more about the importance of this along with examples in my post on advice for a Y Combinator interview.

To give a thorough and compelling pitch of your startup, I recommend the following format.

- Company Name

- What you do

- Who is the customer

- [Optional] 6 to 12 month goal. Clear and measurable, not lofty and vague.

- [Optional] Why you and your team are best for the job

This is so simple that it may seem undignified, yet it’s incredibly important. Time and time again, I’ve seen startup founders try to get fancy when introducing their company, and this almost always leaves the listening investor confused. That is a bad result. If you clearly describe the above bullets, others will understand what you’re doing, and that’s the first critical step to any conversation. It’s harder than it seems, so if you’re pitching your startup, practice on a friend or a stranger and make sure they understand the company.

5-Minute Market Analysis

If you have an idea you’re passionate about, that’s probably sufficient. A useful exercise we did during Y Combinator was a back-of-the-envelope calculation to see how to reach $100 million in annual revenue. This often results in one of two reactions: (1) the founders are pleasantly surprised how feasible it is to grow big OR (2) the founders are shocked how impossible it seems to ever reach such a ridiculous number. If you’re in the second camp, it may be worth reconsidering the business plan, but mostly, it’s important to be aware. It may seem incredibly premature to make these estimates, but it’s the way many investors will judge your business. Investors don’t want a good company, they want the next unicorn, and because companies in Silicon Valley are frequently valued at 10 times revenue, investors will be looking for mental math of at least $100 million in revenue. It’s perfectly acceptable for a founder to not have this goal, and it’s one of many examples of the possible misalignment of incentives between founders and investors, but whether or not this is important to you, it’s important to be aware of this.

Lies you Will Tell Yourself

Finally, I’ve talked to many founders and potential founders, and I’ve changed my own opinions a lot during my own entrepreneurship. I often hear the same things that I believe are almost always misconceptions. The following are statements I hear which I consider false. If you find that you are telling yourself one of the following, and you probably will, then consider whether it’s really true or a convenient excuse.

- I didn’t get hired at Company Y, so I’m not smart enough

- Counterexample: WhatsApp Founders

- Investors won’t like my idea

- Investors won’t give me money

- I can’t live without a salary

- I can’t start without an idea

- There’s nothing I’m uniquely good at

- My idea has been done before, so it’s not worth it.

- See FaceBook, Google, Amazon.

- I can’t compete with the big companies

- “History favors the bold. Compensation favors the meek.” i.e. incumbent CEOs are very risk-averse and conservative

- I can’t start because I’m not a tech / CS person

- I can earn money by starting as a consultant

- I need X (experience, savings, etc) before starting

- Everyone will think I’m cool and I’ll be on Forbes magazine

- Winning is binary

- I’m not technical so I can’t do a software company

- I can’t start a business with my friends

- Only 0.1% of startups succeed, so my chance of success is 0.1%

- If you build it, they will come

- I can’t start a company because I don’t know enough about business.

- I’m too young to start a company.

- I don’t need a great product, I just need great sales and marketing.

- I don’t need great sales and marketing, I just need a great product.

Not Myths

I often hear founders say the following, and I think these are more likely true.

- I won’t make any money for 5 years

- I can get money from friends, family, and fools

- I need to be uniquely able to do this.

- I can’t start because I don’t have a co-founder

- I need to quit my job and go full time

- I need to live in Silicon Valley

- I can’t start because I’m not persuasive or good at pitching, i.e. I can’t sell.

- It will take 3 years to be successful

- If I have a 1% chance of $1B, then my expected value is $10M.

- I don’t need to start a company because I make enough money already.

- If I start a company, I will have to work really really hard.

- If I start a company, I will see more direct output from the effort I put in.

- I can’t start a company because I’m not determined enough.

Conclusion

It turns out I have more to say than expected, and this is what I was able to cover in the workshop. I have many other topics I’d like to cover, so possibly I will write about them in the future. They include:

- Pros and Cons of Starting a Company

- When is the best time to start a company? (spoiler alert: Now)

- Is this the best time in history to be an entrepreneur?

- How and why startups can win

If it’s not already obvious, I highly recommend Paul Graham’s essays. They already cover many of the same topics in a way that is more clear and insightful than I could hope to achieve.